24 April 2015

Countering Intentional Right Wing Disinformation on Social Security, Medicare, and the Affordable Care Act

If you ever believed, or still believe, the Oligarchic Propaganda that

raising the retirement age for Medicare and/or Social Security; and/or

cutting those benefits, is fiscally necessary, or even sensible; OR if

you have been convinced, against all evidence, that the Affordable Care

Act is costing more than expected, or has caused health insurance rates

to rise (it's caused the rate of increase to go down); please read Krugman's piece today

in the New York Times: "Zombies of 2016".

Comcast Time Warner Cable Merger Dead!

So the NYT is reporting the Comcast Time Warner Cable merger is dead, dead, dead (Comcast having pulled out in anticipation of regulatory disapproval). To which I sing: ♫ ♪ Ding Dong! The Witch is Dead! ♫ ♪ The Witch is Dead! ♫ The Witch is Dead!

Only natural for Jeb to distance himself from James Baker

Of course Wannabe Bush III is "distancing himself" from former Sec. of

State James Baker. Baker dared to criticize Netanyahu at a J Street

event recently. He, along with Brent Scowcroft and Lawrence Wilkerson,

are just about the only sane Republicans still in existence in public

life.

And, as sane Americans, all three of these recognize that the views of the current Right Wing government of Israel do not necessarily coincide with the interests of the American people. And that is putting it mildly indeed.

And, as sane Americans, all three of these recognize that the views of the current Right Wing government of Israel do not necessarily coincide with the interests of the American people. And that is putting it mildly indeed.

23 April 2015

Earth Day 2015

On Earth Day, perhaps everyone ought to reflect on the emerging reality

that our world, now 4.6 billion years old, more than 1/3 the age of the

universe, and about 550 million years into the epoch of Complex life, is

something REALLY rare in the Universe. Star Wars and Star Trek are

nothing like reality, which is that the conditions that make for a world

like Earth, with its robust and incredibly dynamic world-ecosystem,

require a host of relatively unlikely conditions. In combination, the

likelihood of a truly Earthlike world becomes very small; so small Earth

may be one of only a handful of such planets in our entire Galaxy of

100 billion or more stars. If these facts don't impel us to develop a

sense of responsibility for the stewardship of our precious planet, I

don't know what could.

(Posted on Earthday to Facebook)

(Posted on Earthday to Facebook)

22 April 2015

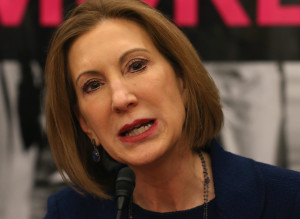

Carly Fiorina, a Joke

Unkind comment alert. This picture of Carly Fiorina -- who announced she's a candidate for president today, not content with running HP into the ground and losing to another Corporate CEO type in the Republican Primary for California governor (at least in Nixon's case it was the general election) -- brings three phrases to mind.

1. Delusions of Grandeur

2. Someone's idea of a token woman in the GOP field

3. Reanimated skull

OK, that last one was pretty mean.

20 April 2015

No Supercivilizations in 100,000 nearest galaxies?

Link.

I am of the view that the apparent absence of "supercivilizations" within a pretty great distance from the Milky Way says virtually nothing about the possibility that spacefaring civilizations, which may have reached a steady state or slow growth but remain essentially undetectable at great distance, could well exist in some numbers. This is one more nail in the coffin, though, for Carl Sagan's prediction that millions of civilizations exist out there in our Galaxy, with its 100-300 billion stars. It's now pretty clear that intelligent life is at best rare.

I am of the view that the apparent absence of "supercivilizations" within a pretty great distance from the Milky Way says virtually nothing about the possibility that spacefaring civilizations, which may have reached a steady state or slow growth but remain essentially undetectable at great distance, could well exist in some numbers. This is one more nail in the coffin, though, for Carl Sagan's prediction that millions of civilizations exist out there in our Galaxy, with its 100-300 billion stars. It's now pretty clear that intelligent life is at best rare.

19 April 2015

David Lauter's Lazy, Lazy Political Analysis in L. A. Times

I was more than a little dismayed to read this sentence in an article in the Los Angeles Times:

"Who wins [in 2016] will almost certainly depend on which proves more

powerful -- the hunger for change or the inexorable demgraphic wave."

The thesis of the article is that changes in demographics favor the

Democrats in the presidential election, but that some undefined "desire

for change" favors the Republicans, as if the nature and direction

of that change, in terms of actual policy that affects real peoples'

lives, made no difference. The entire thesis is unsupported by any

reference to specific evidence, in the form of polling designed to

isolate voter attitudes towards actual Right and Left policy change, and

it's frankly insulting to the intelligence of readers and voters, with

its implicit presumption that people unthinkingly slaver for "change,

any change. " Detailed polling published over the last several years in

fact shows is that the majority of Americans want very specific changes,

which, as it turns out, have not been put in place during the present

Democratic administration largely because of obstruction by Republicans

in Congress. Perhaps it is actually true that the majority of people are

unthinking reactionaries, literally, and will just vote to "throw the

bums" out without a care for who or what replaces them, but if that is

Mr. Lauter's conclusion, the polling he cites referencing "tolerance"

and "preference for a strong leader" is not convincing.

17 April 2015

The Fix is in on TPP

Pretty obvious the FIX is IN. Congress is in the process of waiving its Constitutional

authority to regulate international trade ... again... and signaling that

the very pro-Corporate, undemocratic and anti-working people Trans

Pacific Partnership is likely to be rammed down our throats, after

having been negotiated in secret and quite deliberately kept away from

public scrutiny. I am quite certain that if the majority of the public

knew what was in this agreement, they'd say hell no! and want the SCALP

of their Congress member voting for fast tracking this travesty.

This is one issue where I vehemently disagree with the Obama administration. Obama voted against CAFTA in 2006, but he's drunk the kool aid on corporatist trade deals.

This is one issue where I vehemently disagree with the Obama administration. Obama voted against CAFTA in 2006, but he's drunk the kool aid on corporatist trade deals.

15 April 2015

The principle of Mediocrity and the rarity of intelligent life

The "Principle of Mediocrity", which suggests that the default assumption should be that conditions here on Earth are broadly typical of what you would find anywhere in the universe, is being challenged to its core. Current thinking, based on reading of the evidence from Earth history, seems to indicate that, to the contrary, quite a series of each in itself rather difficult and unlikely transformations had to have occurred for the current planetary environment to have emerged as a stable state. But the broader principle, that the laws of physics and the history of matter and energy, (including the formation and evolution of galaxies), in its broadest view, is much the same throughout the universe (including the great majority of it that is beyond the horizon where light could ever reach us from there).... remains. So, if complex life, including intelligent life, even if the product of a series of necessary but unlikely developments, the combination of which becomes increasingly unlikely, it remains a fact that the sample size is so enormous that we can scarcely imagine it. Rather than giving support to the Religion minded who are biased in favor of finding that life is the unique creation of their Crazy Sky-War God, all it really does is make it likely that complex biospheres like Earth's, capable of giving rise to intelligent beings like ourselves, appear likely to be quite rare in the universe. But rare does not mean unique, necessarily, and from what I understand the combined probabilities amount to "maybe unique in the Galaxy," but not "probably unique in the universe."

Apologies to those who hold such religious views. I am sometimes irremediably snarky in my secularism.

Apologies to those who hold such religious views. I am sometimes irremediably snarky in my secularism.

13 April 2015

No to Democratic Party Clinton Juggernaut

Have to say I strongly object to

the way the DSCC, the House Majority PAC, the DNC, and other supposedly

non-candidate related Democratic organizations all sent out e-mails

urging Democrats to "stand with Hillary," etc. I DON'T stand with

Hillary. I want there to be a primary process, and for real

Progressives, including on foreign policy, to step up and present their

alternative agendas. We do not have anointments of heirs apparent from

ruling dynasties in this country.

I

have requested to be unsubscribed from every one of these, and will

support the Sanders campaign, ActBLUE and the Progressive Campaign

Committee instead.

11 April 2015

Sunshades in Solar Orbit and other seeming pie in the sky ideas to mitigate Climate Change

It seems pretty obvious to me that we are not going to be able to prevent enough

of the Climate Change taking place as a result of the near doubling of

the CO-2 in our atmosphere since the start of the Industrial Age (or

Antrhopocene, if you prefer). The process is too far along, and there is

no way human civilization is going to immediately shut down all

fossil carbon use.

So,

we will have to take various global-scale macro-engineering steps,

sooner or later. This idea, of building sun shades at the Solar LaGrange

point (see link below) is one that will probably engender a reaction of

(almost literally) "pie in the sky" from most people, but, apparently,

space engineering folks have looked at it pretty carefully and it

actually is likely to be feasible.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Space_sunshade

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Space_sunshade

One issue this kind of macroengineering, direct redress of solar heating, does not deal with is the acidification of the oceans.

So it would have to be coupled with other measures, especially, the

rapid move away from fossil carbon fuels, in order to be effective. We

all know our long addiction to fossil carbon simply has to come to an

end, and the sooner the better. We can't just keep on spending the

millions of years long sequestration of carbon that our planet has

accomplished (for good reason), without dire consequences.

But combined measures likely actually could stop major further warming of the Earth, and, gradually, at least, the oceans could be protected. (We will also have to stop expecting them to supply unlimited amounts of wild fish; that era, too, is all but over). And we humans need to get busy working on, and funding the work on, all plausible efforts.

One of which may be helped by this recent discovery: possibly far superior method of producing hydrogen for engine fuels (hydrogen can also be used as a jet fuel). Of course the combustion of hydrogen just yields water. And there is no danger of using up all the oxygen; even if all the fossil carbon on Earth were burned, it would have less than a few tenths of a percent effect on oxygen content of the atmosphere, and even that would be temporary; the Earth's oxygen surplus is built into its bioregulatory systems very robustly). Using hydrogen as a manufactured fuel, as long as fossil carbon isn't involved in making it, is climate-friendly. It's also the case that oxygenic photosynthesis converts water into oxygen, so artificial processes that directly convert hydrogen and oxygen into water are fairly readily offset by the natural systems of the Earth.

https://richarddawkins.net/2015/04/new-discovery-may-be-breakthrough-for-hydrogen-cars/

Another possible temperature mitigation is aerosolization of sea water by ocean going vessels, which could greatly increase, well, fog, over the ocean surface. This is already a major regulatory mechanism by which the Global Feedback System (Gaia) keeps the Earth very much cooler (about 40° C cooler) than it would be in the absence of life: much of the surface mist over the ocean results from bacteria in the water. Anyway, the technology to do this is already in development. But this, too, does nothing about the encroaching acidification of the oceans, which cannot be ignored.

Some

people reflexively balk at "geoengineering," but I think we absolutely

must consider all options. We have done a LOT of geoengineering since we

started burning coal, oil, and natural gas on a massive scale, and it

promises to wreck our world as cozy and comfortable habitat for

humanity. Either we get smart, and think these things through carefully,

control for all effects, and proceed cautiously to do what has to be

done, or we fail, and billions will likely die in the catastrophe that ensues. That's the choice. Reflexive rejection of "geoengineering" is not an option.

But combined measures likely actually could stop major further warming of the Earth, and, gradually, at least, the oceans could be protected. (We will also have to stop expecting them to supply unlimited amounts of wild fish; that era, too, is all but over). And we humans need to get busy working on, and funding the work on, all plausible efforts.

One of which may be helped by this recent discovery: possibly far superior method of producing hydrogen for engine fuels (hydrogen can also be used as a jet fuel). Of course the combustion of hydrogen just yields water. And there is no danger of using up all the oxygen; even if all the fossil carbon on Earth were burned, it would have less than a few tenths of a percent effect on oxygen content of the atmosphere, and even that would be temporary; the Earth's oxygen surplus is built into its bioregulatory systems very robustly). Using hydrogen as a manufactured fuel, as long as fossil carbon isn't involved in making it, is climate-friendly. It's also the case that oxygenic photosynthesis converts water into oxygen, so artificial processes that directly convert hydrogen and oxygen into water are fairly readily offset by the natural systems of the Earth.

https://richarddawkins.net/2015/04/new-discovery-may-be-breakthrough-for-hydrogen-cars/

Another possible temperature mitigation is aerosolization of sea water by ocean going vessels, which could greatly increase, well, fog, over the ocean surface. This is already a major regulatory mechanism by which the Global Feedback System (Gaia) keeps the Earth very much cooler (about 40° C cooler) than it would be in the absence of life: much of the surface mist over the ocean results from bacteria in the water. Anyway, the technology to do this is already in development. But this, too, does nothing about the encroaching acidification of the oceans, which cannot be ignored.

08 April 2015

Lenton & Watson: predictions regarding life elsewhere

I found the following, slightly edited excerpt from Lenton & Watson's Revolutions that Shaped the Earth (Oxford, 2010), so interesting that I post it despite its length in hope that some few others might also find it compelling. I added a couple of notes in italics inside square brackets.

6.7 Predictions regarding life elsewhereIn this section we make some predictions from the assumptions of the anthropic model, concerning unknowns about life elsewhere. These are interesting in themselves, and since they are open to testing in the future as our knowledge increases, they could help establish or disprove the anthropic view of Earth history which we have been exploring.So let us now review those fundamental assumptions and what they imply. The main one is that the pace of evolution on Earth, to ourselves, as complex, intelligent observers, has been constrained by the necessity to pass through a small number of intrinsically very unlikely events. These are sufficiently improbable that a priori, they would not have been expected to all occur during the limited time that the Earth will be inhabitable. However, on Earth, by lucky chance, they occurred considerably more quickly than was to be expected, which is how we came to be here and are able to ask these questions.This idea has implications for how much life, of what kind, and around what kind of stars, we ought to expect to find in our part of the universe. These implications have some hope of being tested, because over the next few decades, astronomers and the space agencies will be putting huge effort into discovering and characterizing extra-solar planets, using telescopes both at the Earth's surface and in space. Ultimately, the goal will be to spectroscopically analyze the atmospheres of any planets that are found, looking for the raw materials we know to be necessary for life, such as water and carbon dioxide. But the investigators will also be hoping to detect ‘bio-signatures’ — in particular, ozone. This is thought to be diagnostic for oxygen, which itself is difficult to detect in a planetary atmospheres, since it does not exhibit visible or infrared absorption lines. Ozone however, is comparatively easy to detect and is expected to be present only when there is also significant oxygen.The planet-finding missions of this century will build on ideas going back to the middle of the last one. Jim Lovelock was the first to suggest that analysis of planetary atmospheres could be used to diagnose the presence of life, an idea he developed with the philosopher Dian Hitchcock. They pointed out that the best bio-signature is not just one gas, but the presence of two that are in strong chemical disequilibrium with one another. They suggested that if you trained an infrared telescope on the Earth, you would be able to detect the simultaneous presence of ozone (hence oxygen) and methane in the atmosphere. Since methane and oxygen react with one another rapidly as carbon dioxide and water, you would be able to deduce that something must be producing them from their reaction products with equal rapidity, and this something must be life. (Actually, it's not just life, but [oxygenating] photosynthesis, that you would have diagnosed from the measurement. Some twenty-five years later, in one of his last papers, Carl Sagan and colleagues demonstrated that the technique works for the Earth, using the instruments on the Galileo spacecraft looking back to Earth while on its way to Jupiter.One way or another, in the first half of the twenty-first century, we are going to get lots of evidence that bears on the habitability of nearby solar systems. There are some 250 star systems within thirty light years of Earth. Let's be optimistic and assume that we find many of them have planets in their habitable zones. What does the anthropic theory suggest we should find when we examine them with these planet-finder missions?We suspect prokaryote life is not so common as to always arise on a planet within a habitable zone, but it involves at most one really difficult step (you'll recall, we can't really be sure it is critically difficult), and we consider that there is a reasonable chance that it will have arisen on some of the systems we will be able to observe. Pre-oxygenic photosynthesis is not apparently a critical step, and it arose relatively quickly on Earth after prokaryotes were established. This would ensure an energetic biosphere to exist, with a characteristic atmosphere full of exotic trace gases such as hydrogen sulfide and methane as well as carbon dioxide and water. We have some hope, therefore, of being able to detect a few planets that have this kind of biosphere, during the next few decades.But oxygenic photosynthesis was a difficult step — it may be genuinely critical in the sense of the model, in which case it would occur on, at most, one in ten of the planets that took the first step, and more probably many fewer. In a sample of a few hundred planets we would be lucky to observe any that took this second step. We conclude that most likely we will not find any evidence for abundant oxygen on any of these target planetary systems.There are some interesting predictions that also come from the anthropic model. For example, if complex life is rare, it is likely that Earth will be found to be one of the most favorable possible spots for it to have evolved, a cosmic Garden of Eden. This leads to an interesting question: Is there anything about our Solar System that marks it out as unusual compared to most others, and might make it particularly conducive to hosting complex life? Of course it has Earth, ideally situated in the habitable zone, and it may be that few other solar systems have such planets — but we don't know as yet what the distribution of planetary systems is, so we must put that aside for the moment. Is there anything else unusual about the Solar System?As a matter of fact, there is: the Sun is an unusually bright star, brighter than more than 90% of its neighbors. [A histogram of the 250 local stars within 10 parsecs (about thirty-three light years) of the Sun shows that]: the Sun is well out on the bright limb of the distribution. This is a quite strong indication that most of the stars in our neighborhood, which are cool and dim type-M red dwarfs, with on average only about half the mass of the Sun, are really not as suitable for hosting complex life as our bright yellow type-G star. As this is all the more surprising because type M stars do have one factor that ought to make them more hospitable for complex life, and that is their long life span. Smaller stars burn their nuclear fuel more slowly, and the lifetime on the main sequence of type-M stars is typically (more than) twice as long as the Sun’s. According to our thinking and the evidence of our own planet, the shortness of the habitable period is a major factor limiting the chances that complex life develops. And yet we have awoken to find ourselves orbiting a bright, showy, short-lived firework of a type-G star, rather than a long-burning but dim and dull type-M.We predict, therefore, that there is another factor or factors which make it difficult for life to develop to complexity around fainter stars, and explains why we don't find ourselves orbiting one. In fact there are several possible disadvantages to living around a type M star, but it's not clear as yet that any of them are so severe that they can tip the balance against them as good nurseries for life. Astrobiologists have recently been looking harder at type-M stars, as possible targets for SETI searches, for example, and the discussion below owes much to some recent papers from a symposium on the subject.The habitable zone of a red dwarf is much closer to the parent star than is the Sun's — stars rapidly becoming much less bright as we go towards smaller size, and a star half the mass of the Sun emits only a few percent of its energy. A habitable planet around a M star would therefore have to huddle close to it for warmth, orbiting closer than Mercury to the Sun. Here, it will become tidally locked; its rotation slowed by internal energy dissipation until it equals the orbital, and the same face is always to the star. (The Moon of course is tidally locked to the earth, the reason why we always see its same face). Tidal locking will mean that there will be permanent huge temperature extremes on the planet, between the boiling daytime and the freezing, nighttime faces. If the atmosphere and ocean are not very efficient at transporting heat, this will mean that only a narrow strip around the terminator will actually be inhabitable, and we would expect that all the water on the planet would end up frozen out on the cold side by a 'cold trap' effect. However, with a sufficiently thick and mobile atmosphere, this fate could be avoided. [Note: it may not, according to some calculations, necessarily be the case that planets orbiting Class M dwarfs at the habitable zone distance will be tidally locked, but their rotational periods will be longer compared to their periods of revolution than is the case with Earth, possibly even longer than their 'year'].Another problem may simply be that small stars tend to have small planets. The mass of the central star will certainly be related to the mass of the nebula that accretes around it, hence to the size of any planets that eventually form. As we have seen, it is critically important that it planet is big enough to hold onto a sufficiently thick atmosphere, and also to generating internal geothermal he to power plate tectonics (tidal dissipation would help there by adding a source of heat to the interior). We don't know enough about the planetary formation process to make very firm predictions, however. Current ideas tend to favor a picture of planetary formation as quite stochastic in nature, so while we certainly would expect a tendency for smaller stars to have smaller planets, perhaps there is nothing against a star half the size of the Sun having a rocky planet as big as the Earth.There is a third problem for life around a faint star, as first pointed out by Ray Wolstencroft and John Raven. This one seems to be a really serious barrier to the development of complex life. Red dwarfs are the color they are because they are cooler than the Sun, typically only reaching about half its surface temperature. This means that the photons they emit are lower in energy. Chlorophyll makes full use of the high-energy photons emitted by the sun, absorbing strongly in the high-energy blue region of the spectrum, (as well as in the red, leaving the central, green wavelengths reflected — hence its characteristic color). But as we've discussed, for photosynthesis to split water, a high-voltage must be generated by the photo systems in plants, and even on Earth. This has required that two photo systems be coupled together. Under a much cooler star, very few high-energy photons would be available, and it is likely that three or even four such systems would have to be coupled together to accomplish the task of splitting water. But the evidence is that it was no simple task for evolution to arrive at water splitting photosynthesis even on Earth, so it may be much more difficult still to accomplish this under the light of a cooler star. What this might mean is that though type-M biospheres may evolve photosynthesis, they would find it nearly impossible to evolve the water-splitting variety, and, as we'll discuss in future chapters, without oxygen, there is very unlikely to be animals, let alone intelligent animals.[At this point the authors might well have also mentioned the additional issue that red dwarf stars typically emit powerful flares, which, with the otherwise potentially habitable planets being as close as they are, could be highly disruptive to any life that might exist on the surface of those planets].6.8 SummaryOur speculations in this chapter lead us to predict that simple (prokaryote) life might be moderately abundant in the universe at large — or possibly not, depending on just how difficult evolution to this first critical step [turns out to be]. Whether prokaryotes are rare or common, however, complex life will be rare. This idea has been named the Rare Earth Hypothesis, since it was put forward in a book of that name by Peter Ward and Donald Brownlee. Our analysis agrees very much with their thesis, though we find their arguments frustratingly qualitative. Ward and Brownlee argue their case based on the fortunate position of the Earth, our possession of a good-size moon, a friendly big brother planet in the shape of Jupiter, etc. The difficulty with their argument is precisely the 'self-selection bias' problem that we've tried to tackle in this and the previous chapter. We see that the earth has these attributes and (perhaps) that they have contributed to the evolution of complex life on her, but with only a single example of an inhabited planet, we don't see how to decide which of these properties are really necessary for us to be here, and which are not.Maybe other solar systems have even more favorable circumstances? Anyway, we are subscribers to the Rare Earth Hypothesis, and expect to be born out when we eventually start to get data from other star systems on the atmospheres of Earth-like extrasolar planets. However, while waiting a decade or two that it is going to take before this data begins to come in, we hope that the more formal approach that we have taken here can provide some theoretical support for the 'Rare Earth’ view.

07 April 2015

Oxygen-producing photosynthesis as a Critical Step in the evolution of life on Earth

Below is a slightly edited excerpt from The Revolutions that Made the Earth by Watson & Lenton (pp. 88-89). They are making the case here that the evolution of oxygen-producing photosynthesis is one of what they refer to as critical steps

in the evolution of life on Earth, i.e., events so unlikely that if you

were to 'play the tape over' as Stephen Jay Gould described in his 1989

book Wonderful Life, they would likely not happen again.

(If you think about it, that implies that most planets where life might

have evolved based on initial conditions will not have experienced the critical steps described).

I just love this stuff. What's really amazing is that they make a pretty good case, based on statistical reasoning pioneered by Brandon Carter in the 1980s, that the critical steps they argue occurred on Earth (evolution of the genetic code, this one, emergence of endosymbiotic eukaryotes, and the evolution of language-using observer sophonts (i.e., us)), are all so unlikely that they would not be expected to occur in the 4 billion years or so that Earth has been habitable (even if stretched to add in the 100 to 500 million years its habitability has yet to go). In fact, all four are far more unlikely even than the origin of life itself, which actually occurred just about as quickly as it was physically possible for it to have done. (Setting aside the possibility of panspermia, i.e., extraterrestrial origin of life on Earth, or miracles; the first being difficult to assess but generally considered unlikely and the second being beyond the realm of science). Similarly, the evolution of macrobiota, meaning visible multicellular plants and animals, which is usually front and center in any history of life on Earth, is almost certainly not a critical step, as there is good evidence that it happened independently several times. But the upshot is that at least four entirely unique, and very, very unlikely evolutionary developments, each of which required the ones before to have happened, and in that sequence, all happened in the evolution of life on Earth. (Think about that: without the genetic code, photosynthesizing bacteria could not have evolved; without photosynthesis, there would be no oxygen atmosphere, and eukaryotes could not have evolved; without eukaryotes, intelligent animals, which are necessarily eukaryotic, could not have evolved; so the sequential order is necessary). The assessment of improbability is based on timing and uniqueness. The chance of all four occurring on any given potentially habitable planet, in order, and during the time the planet remains habitable (that is, before its star gets too hot to allow life there, which is the universal fate of habitable planets)... is truly miniscule. Of course, what that doesn't address is the likelihood that other, unknown and potentially equally remarkable, critical steps could be occurring or have occurred elsewhere, leading to unimaginably different biospheres. I suspect if and when humanity encounters life that did not originate on Earth, we will be simply amazed by how different the initial potentials can turn out.

[W]e think the case for [oxygenic photosynthesis’] being a critical step is very strong. Photosynthesis powers the planet, and we’ll describe [later in the book] the evolution of this remarkable mechanism, and just how profoundly it has transformed the Earth system. Here we simply want to establish reasons for believing it may have been one of our critical steps, using the two criteria of uniqueness and timing by which we hope to recognize such transitions.

The bacterium that first produced oxygen by splitting water with sunlight coupled together to earlier-evolved photosynthetic pathways, called photosystems I and II. In addition it possessed a unique enzyme containing four manganese atoms, called the water-splitting complex. The biochemistry of oxygenic photosynthesis is staggeringly beautiful and complex, involving the absorption of a total of eight protons in the process of splitting two water molecules to release one molecule of oxygen. Among all the prokaryotes, only the cyanobacteria evolved this ability, and later, they became the ancestors of all the chloroplasts in all the eukaryote algae and plants [on Earth].

The evidence is consistent with the original invention having occurred just once, with no sign that it evolved separately ever again, and the water-splitting complex has remained essentially unchanged over billions of years. This is significant, because oxygenic photosynthesis is an amazingly useful trick for any organism to possess, since it enables the uptake of carbon and the production of energy using just light, carbon dioxide and water — three of the most abundant resources on the surface of the planet. An organism that can do it is well equipped to make a living in most habitats on Earth, and, therefore, you might suppose that if it were easy in evolutionary terms, it might have happened more than once. Since it did not, we can assume that it was no everyday event: this was a red-letter day for life on Earth.

I just love this stuff. What's really amazing is that they make a pretty good case, based on statistical reasoning pioneered by Brandon Carter in the 1980s, that the critical steps they argue occurred on Earth (evolution of the genetic code, this one, emergence of endosymbiotic eukaryotes, and the evolution of language-using observer sophonts (i.e., us)), are all so unlikely that they would not be expected to occur in the 4 billion years or so that Earth has been habitable (even if stretched to add in the 100 to 500 million years its habitability has yet to go). In fact, all four are far more unlikely even than the origin of life itself, which actually occurred just about as quickly as it was physically possible for it to have done. (Setting aside the possibility of panspermia, i.e., extraterrestrial origin of life on Earth, or miracles; the first being difficult to assess but generally considered unlikely and the second being beyond the realm of science). Similarly, the evolution of macrobiota, meaning visible multicellular plants and animals, which is usually front and center in any history of life on Earth, is almost certainly not a critical step, as there is good evidence that it happened independently several times. But the upshot is that at least four entirely unique, and very, very unlikely evolutionary developments, each of which required the ones before to have happened, and in that sequence, all happened in the evolution of life on Earth. (Think about that: without the genetic code, photosynthesizing bacteria could not have evolved; without photosynthesis, there would be no oxygen atmosphere, and eukaryotes could not have evolved; without eukaryotes, intelligent animals, which are necessarily eukaryotic, could not have evolved; so the sequential order is necessary). The assessment of improbability is based on timing and uniqueness. The chance of all four occurring on any given potentially habitable planet, in order, and during the time the planet remains habitable (that is, before its star gets too hot to allow life there, which is the universal fate of habitable planets)... is truly miniscule. Of course, what that doesn't address is the likelihood that other, unknown and potentially equally remarkable, critical steps could be occurring or have occurred elsewhere, leading to unimaginably different biospheres. I suspect if and when humanity encounters life that did not originate on Earth, we will be simply amazed by how different the initial potentials can turn out.

05 April 2015

Lenton & Watson, Revolutions that Made the Earth, and the prevalence of intelligent life in the universe

I'm reading Lenton & Watson, Revolutions that Made the Earth (Oxford,

2010). It's a whole evolutionary history, from an Earth-System ("Gaia")

point of view. Very interesting. Although hardly central to their

thesis, they agree in general with Brownlee & Ward (Rare Earth)

that complex life may be very rare in the universe. The "Archean" revolution, (Genetic Code, origin of life,

replicating organisms, some kind of sustainable autotrophy; the

emergence of the enzyme Rubisco, or something very like it); and

probably the second "revolution" that resulted in photosynthesis (not

necessarily oxygen-producing, there are at least two other systems still

extant on Earth).... may be relatively "easy." Thus living worlds that

have accomplished these developments may be common elsewhere in the

universe. Other "revolutions," however, including the endosymbiotic

adaptation that resulted in eukaryotes, the remarkable combination of

Photosystem I and Photosystem II to create a really powerful system of

oxygenating photosynthesis (resulting in the evolution of cyanobacteria,

which were subsequently endosymbiotically combined with eukaryotes to

produce plants), may have relied on chance circumstances sufficiently

unlikely that comparable events may not frequently occur in the

history of life elsewhere, such that complex life may be quite rare in

the universe. The evolution of macroscopic organization, i.e., the

Cambrian Explosion, they seem to treat as more or less inevitable, but

it couldn't have happened without these other, less likely, earlier

revolutions. Then there's the Great Fourth Biological Revolution: the

emergence of human culture. We are already processing 1/10 of the

100,000 gW/sec. of energy that the entire rest of the biosphere

produces, and, as Lovelock discusses in his most recent book (A Rough Ride to the Future),

our "rate of evolution" (transmitted as information outside our bodies,

not just our genes), is about 1 million times faster than previous

biological evolution. So our existence is a very big deal in the history

of life on earth, objectively. (Many people are resistant to this idea,

but if you really think about it, it's actually undeniable). These guys

seem to think this development is also probably rather unlikely.

In 600 million years, since the emergence of macroscopic animals, no

other animal, including our close relatives the chimps and gorillas,

even came close. Hard to say, but you could imagine, as Stephen Gould

used to analogize, "replaying the tape," a number of times, even

starting with, say, the Mesozoic, and not getting the equivalent of

humans most of the time.

Incidentally, I am not at all sure that the first of the "revolutions," which Lenton and Watson seem to treat as pretty likely, namely the origin of life at all (what they refer to as "Inception") isn't just possibly the most unlikely of all. We just don't know. Other than the fact that it seems to have occurred on Earth at just about the earliest physically possible date, I've not seen an explanation for why this should be considered an "easy" transition. From non-life to life? Seems to me quite conceivable, as old fashioned thinkers used to argue, that this one could turn out to have been spectacularly unlikely. We modern folks (including me) prefer to think that life is common in the universe, but there is no real hard evidence for that presumption.

All

of this has implication for our favorite topic, the prevalence, or

non-prevalence, of human-equivalent civilized life elsewhere in the

universe. Of course no one knows, for sure. But there is a pretty robust

intellectual case for the idea that even planets as favorably situated

at the outset for the emergence of life as Earth was at the outset, may

only quite rarely result in the emergence of intelligent beings and

technological civilizations. Incidentally, I am not at all sure that the first of the "revolutions," which Lenton and Watson seem to treat as pretty likely, namely the origin of life at all (what they refer to as "Inception") isn't just possibly the most unlikely of all. We just don't know. Other than the fact that it seems to have occurred on Earth at just about the earliest physically possible date, I've not seen an explanation for why this should be considered an "easy" transition. From non-life to life? Seems to me quite conceivable, as old fashioned thinkers used to argue, that this one could turn out to have been spectacularly unlikely. We modern folks (including me) prefer to think that life is common in the universe, but there is no real hard evidence for that presumption.

Lurking behind all of this ratiocination is one or other level of the anthropic principle. We cannot, of course, really say whether the combined probability of all of these "unlikely" revolutions adds up to the Earth being a nearly impossible miracle, or something much more likely to occur, in broad outlines. Because, it almost goes without saying at this point, but for all of this having occurred, just as it did, we would not be here to think about it. So we cannot assess, without more information about other instances of life, how likely rough alternatives may or may not have been, which might have led to our rough equivalents. Or not.

The

authors are relying on two things. The complexity of the adaptations

involved, which they plausibly translate into a measure of the

"difficulty" for evolution to come up with a specific major adaptive

change. And the other is that certain kinds of change, like the

evolution of complex body plans from single celled organisms, apparently

happened over and over again, which is more than a hint that it's an

"easy" development. But the "revolutions" they consider to be "unlikely"

occurred only once, and usually after long periods of time at any point

during which they could have happened but did not.

•

03 April 2015

On CO-2 and long range climate change, and the role of humanity as a key element of Gaia

I've posted several comments deriving from the rambling little book by James Lovelock I read recently, A Rough Ride to the Future. I haven't read all of his books on his Gaia hypothesis, so I am assuming some of what he says in this book is recycled.

Be that as it may, he makes an interesting point about the Earth Self-Regulatory (Feedback) System ("Gaia") and CO-2. For the past million years or so, the Earth has been in a glaciation state about 80% of the time. Apart from the present anthropogenic climate change, we are in the midst of what would otherwise almost certainly have been a relatively brief interglacial. (Warmer period, usually only 15-20% of the duration of glaciations, during which most of the ice melts, sea levels rise, and the Earth's average temperature rises; currently about 16° C).

According to Lovelock, this pattern of repeated glaciation, although partly known to be caused by changes in the earth's orbit and precession, is also part of the long term feedback system. "Gaia" is (was) keeping the World colder because, counterintuitively, cooler tropical waters, in particular, allow a cooler world to maximize biomass and biodiversity. Even in the (geographically shifted) more temperate areas, there is more forest and more robust life overall during glaciations. One major factor is that during glacial maxima, the sea level worldwide is nearly 100m (!) lower, which means there were huge areas, almost an entire additional continent, of land that's now submerged.

In fact, during such maxima, the Self Regulatory System keeps CO-2 levels very close to the lowest possible. At the height of recent glaciations, it was about 180 ppm, which is the LOWEST it has EVER been, at least since the inception of an oxygen rich atmosphere, and before that it was probably MUCH higher anyway.

What this means is that until recently the Earth was keeping CO-2 as low as possible in order to keep the world cool. This is in part to counterbalance the slow-exponential rise in the brightness of the Sun. A billion and a half years or more ago, the amount of sunlight striking the surface of the Earth's atmosphere (the "Solar Constant") was about 1 kW/m^2, yet the greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, principally water vapor and methane, usually kept the surface temperatures higher than they are today (although there were periods of intensive glacial activity scattered in time). Today, it's about 1.35 kW/m^2. The lower CO-2, low methane levels, and low humidity worldwide on average, keep the Earth cooler. In as little as 100 million years, the Solar Constant will be about 1.5 kW/m^2. At that point (or somewhat later, but the exact date isn't the point), in order to keep the oceans from getting so warm that water vapor will induce a runaway greenhouse and turn the Earth into a Venus, the Earth's Self-Regulatory System will have to lower CO-2 levels to zero. But at zero, plants cannot live in the atmosphere, so macroscopic life on land will disappear.

This may seem arcane, but what it means is that the Earth has been fighting global warming, caused by the SUN, for epochs, and it will start losing the battle in a much shorter time than the time in which complex life, much less simpler life, has existed on Earth. The Earth is likely doomed to a runaway heat death, no matter what its self-regulatory systems do. The wildcard being humans, who may, by space engineering, be able to do something about all this (Lovelock scarcely mentions space engineering, but I see it as virtually inevitable).

Lovelock is optimistic, and sees human beings as an essential element of Gaia, and its future ability to regulate climate and other factors to keep the Earth habitable. Sounds right to me, but I think our role as the only Earth life capable of acting in the wider Solar System, not just on Earth, will be key. For those inclined to a teleological view of the nature and role of humanity in the Universe, that is probably it: we are here to broaden Gaia's game so life can persevere more than a short span in the scheme of things into the future, and, I'll throw in, probably equally importantly (Lovelock ignores this completely), we are here to be the Earth's gonads, or flowers, if you prefer: to replicate Earthian biospheres elsewhere, by transporting the seeds of life to other suitable locations, either in the Solar System, or beyond (or both). (This idea was promoted by the late Timothy Leary, who, despite addling his brain a bit with LSD, was quite the visionary thinker).

Be that as it may, he makes an interesting point about the Earth Self-Regulatory (Feedback) System ("Gaia") and CO-2. For the past million years or so, the Earth has been in a glaciation state about 80% of the time. Apart from the present anthropogenic climate change, we are in the midst of what would otherwise almost certainly have been a relatively brief interglacial. (Warmer period, usually only 15-20% of the duration of glaciations, during which most of the ice melts, sea levels rise, and the Earth's average temperature rises; currently about 16° C).

According to Lovelock, this pattern of repeated glaciation, although partly known to be caused by changes in the earth's orbit and precession, is also part of the long term feedback system. "Gaia" is (was) keeping the World colder because, counterintuitively, cooler tropical waters, in particular, allow a cooler world to maximize biomass and biodiversity. Even in the (geographically shifted) more temperate areas, there is more forest and more robust life overall during glaciations. One major factor is that during glacial maxima, the sea level worldwide is nearly 100m (!) lower, which means there were huge areas, almost an entire additional continent, of land that's now submerged.

In fact, during such maxima, the Self Regulatory System keeps CO-2 levels very close to the lowest possible. At the height of recent glaciations, it was about 180 ppm, which is the LOWEST it has EVER been, at least since the inception of an oxygen rich atmosphere, and before that it was probably MUCH higher anyway.

What this means is that until recently the Earth was keeping CO-2 as low as possible in order to keep the world cool. This is in part to counterbalance the slow-exponential rise in the brightness of the Sun. A billion and a half years or more ago, the amount of sunlight striking the surface of the Earth's atmosphere (the "Solar Constant") was about 1 kW/m^2, yet the greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, principally water vapor and methane, usually kept the surface temperatures higher than they are today (although there were periods of intensive glacial activity scattered in time). Today, it's about 1.35 kW/m^2. The lower CO-2, low methane levels, and low humidity worldwide on average, keep the Earth cooler. In as little as 100 million years, the Solar Constant will be about 1.5 kW/m^2. At that point (or somewhat later, but the exact date isn't the point), in order to keep the oceans from getting so warm that water vapor will induce a runaway greenhouse and turn the Earth into a Venus, the Earth's Self-Regulatory System will have to lower CO-2 levels to zero. But at zero, plants cannot live in the atmosphere, so macroscopic life on land will disappear.

This may seem arcane, but what it means is that the Earth has been fighting global warming, caused by the SUN, for epochs, and it will start losing the battle in a much shorter time than the time in which complex life, much less simpler life, has existed on Earth. The Earth is likely doomed to a runaway heat death, no matter what its self-regulatory systems do. The wildcard being humans, who may, by space engineering, be able to do something about all this (Lovelock scarcely mentions space engineering, but I see it as virtually inevitable).

Lovelock is optimistic, and sees human beings as an essential element of Gaia, and its future ability to regulate climate and other factors to keep the Earth habitable. Sounds right to me, but I think our role as the only Earth life capable of acting in the wider Solar System, not just on Earth, will be key. For those inclined to a teleological view of the nature and role of humanity in the Universe, that is probably it: we are here to broaden Gaia's game so life can persevere more than a short span in the scheme of things into the future, and, I'll throw in, probably equally importantly (Lovelock ignores this completely), we are here to be the Earth's gonads, or flowers, if you prefer: to replicate Earthian biospheres elsewhere, by transporting the seeds of life to other suitable locations, either in the Solar System, or beyond (or both). (This idea was promoted by the late Timothy Leary, who, despite addling his brain a bit with LSD, was quite the visionary thinker).

HRC backs Obama on Iran Deal

One sees where Clinton has "backed" Obama on the Iran deal. One would hope so, but I have to admit it was conceivable that she wouldn't, given some of her past statements.

The Iran Nuclear Deal -- Comment

Let us recollect some things, on this Passover/Good Friday (not my religions, but regardless). Back in 2001-2003, the Iranians, who were alarmed by the Salafist radical terrorists, including the 9/11 highjackers, and the prospect that the US would go nuts and destabilize the whole region, tried to start some meaningful talks with the US government about improving relations and actually cooperating in, among other places, Afghanistan. De Facto President Cheney's response: "Go screw yourselves." What he actually said, publicly, was "We don't deal with evil." The Cheney/Bush administration proceeded to fight two wars primarily for the BENEFIT of Iran (whatever their misguided rationale may have been), while ignoring Iran completely diplomatically. Which, of course, had the effect of strengthening the theocratic dictatorship there, and actually increasing their hold on power over the Iranian people. And it also drove them to surreptitiously work on developing nuclear weapons capability.

In 2008 the American people had the good sense to elect a Democratic president; one who made clear he preferred to engage in diplomacy, as a first resort, with military power only as a last resort. The Bought and Paid For Party of course has obstructed and stymied his efforts wherever possible, but finally, much credit to SOS Kerry (who has done a much better job than Hillary Clinton, it must be said), this past week, a comprehensive framework for a nuclear deal that will, if implemented as outlined, guarantee that the Iranians cannot develop nuclear weapons for at least 15 years. Or, actually more likely, ever, since the Iranians (unlike Israel, which developed thermonuclear weapons in secret) IS a signatory to the Non Proliferation Treaty. Iran has now agreed to the most invasive inspection regime in history, with NO EXPIRATION DATE.

Let me be totally clear. If a Ronald Reagan (or, more accurately, a Jim Baker) had concluded this deal, there would be bipartisan cheers all around, Time Magazine would put him on the cover with "Greatest Peacemaker of the Century" or some such thing. The implementation of the agreement would sail through both houses of Congress with overwhelming majorities. A Nobel Peace Prize would be in the offing.

But because of the irrational, visceral hatred of Republicans for this president and their preference for actually working against the interests of our nation in the belief that it will further their narrow, oligarchic and plutocratic political interests, this president and his administration has an uphill fight on its hands to convince Congress to do what is necessary to seal this diplomatic VICTORY... for that is what it is... by implementing its provisions.

And that, my friends, is our national disgrace.

In 2008 the American people had the good sense to elect a Democratic president; one who made clear he preferred to engage in diplomacy, as a first resort, with military power only as a last resort. The Bought and Paid For Party of course has obstructed and stymied his efforts wherever possible, but finally, much credit to SOS Kerry (who has done a much better job than Hillary Clinton, it must be said), this past week, a comprehensive framework for a nuclear deal that will, if implemented as outlined, guarantee that the Iranians cannot develop nuclear weapons for at least 15 years. Or, actually more likely, ever, since the Iranians (unlike Israel, which developed thermonuclear weapons in secret) IS a signatory to the Non Proliferation Treaty. Iran has now agreed to the most invasive inspection regime in history, with NO EXPIRATION DATE.

Let me be totally clear. If a Ronald Reagan (or, more accurately, a Jim Baker) had concluded this deal, there would be bipartisan cheers all around, Time Magazine would put him on the cover with "Greatest Peacemaker of the Century" or some such thing. The implementation of the agreement would sail through both houses of Congress with overwhelming majorities. A Nobel Peace Prize would be in the offing.

But because of the irrational, visceral hatred of Republicans for this president and their preference for actually working against the interests of our nation in the belief that it will further their narrow, oligarchic and plutocratic political interests, this president and his administration has an uphill fight on its hands to convince Congress to do what is necessary to seal this diplomatic VICTORY... for that is what it is... by implementing its provisions.

And that, my friends, is our national disgrace.

02 April 2015

Lovelock: A Rough Ride to the Future

No question Gaia hypothesis originator James Lovelock's book, A Rough Ride to the Future,

is provocative and interesting, but I do get the sense that, at 95, he

has come to see himself as an oracle of elder wisdom. This mostly takes

the form of a certain degree of contrariness, coupled with a healthy

prescription for continuing skepticism. He has changed his views on

Climate Change, to the point that he stands in opposition to a lot of

the conventional wisdom about what should be done.

He

points out, probably quite correctly, that the complex

partial-differential equation dynamic models based on less than ideal

data which have been used to model the effects of Climate Change are

just not reliable. Already, they have not predicted (both up and down)

changes that have occurred since 2000. So, we are, in effect, flying

blind.

He

is not a Climate Change denier, though. He says that climate change

induced by higher levels of CO-2 is unpredictable, but unavoidable. He notes that it has been the "goal" of Gaia

feeback systems since at least the beginning of the current 1 million

year ice age cycle, to minimize CO-2 in order to keep the world as cold

as practicable, because that actually enhances the biodiversity and flourishing of Earth life. It is simply already

impossible to prevent a significant disruption of the Earth's

pre-industrial climate. That disruption is already well underway, as we

all can see around us if we're willing to take in the obvious. He takes a

very dim view of weaning the world from carbon in favor of renewable

energy, which he says is not efficient or practical (except nuclear

power). Not that many of his colleagues in the climate

science/ecological sciences communities agree with THAT. Mostly, in my

opinion, he is highly unrealistic about the prospects of moving large

populations into new regions. He thinks flooding of places like

Bangladesh is inevitable, and that people will have to migrate.

Maybe

he's right, but after criticizing the models being used to game out

climate change, he pretty much offers only intuition in place of them

(and this from the guy who invented Daisyworld, which is a mathematical

model of how the biosphere regulates climate!). He says that belief by

non-scientifically trained people that rolling back CO-2 to 18th century

levels is even possible, or that it would result in the immediate shift

back to the climate regime of that time, is just naive.

Personally,

I suspect, as I've said before, that he is right that climate change is

not going to be easily controlled, is unpredictable (we might get

lucky; but we have to allow for the likelihood that we will be very unlucky), and that we are going to almost certainly have to do mitigation, including geoengineering, eventually.

He mentions the possibility that private actors may take matters into

their own hands, citing, as an example, the invention of technology

(already done) that can aerosolize seawater on a pretty large scale.

Attached to ships, it could be possible to dramatically increase the low

level cloud cover over the oceans. But what effect that would

have is not really predictable either; it could actually cause drought

in areas currently producing much of the world's food, for example. But I

suspect that when, not if, things get bad in certain places in

the world where the powerful hang out, a lot of questionable and

possibly dangerous things will be done. Hence, a rough ride indeed is

before us.

All

of this is in the context of his view that technological evolution

since 1700 or so has outstripped DNA based biological evolution, and

even superseded it as the dominant form of life-change. We don't

perceive this clearly, because we are inured to the pace of change. But

the rate of rapid evolution shows signs of leveling off, indicating that

a new steady state is emerging. Climate change is part of that. But

that doesn't mean that the next few decades won't be extremely

disruptive. To the contrary, they almost certainly will be.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)